December 2022 Case Study

by Adam Rosenfeld, MD

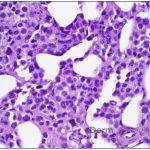

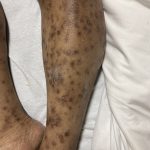

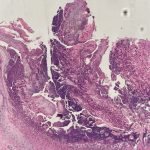

A 43-year-old gentleman with known history of Langerhans cell sarcoma (s/p numerous rounds of chemotherapy and targeted therapy) presented to the ED with a 1-month history of worsening back pain and malaise. He was admitted due to concern for sepsis and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Dermatology was consulted for painful lesions on his legs that the patient had noticed several months prior to presentation. On examination, the patient had multifocal ulcerations on his bilateral thighs, with overlying fibrinous material (figure 1). A punch biopsy was done on one of these ulcerations (figure 2). Although these ulcerations could represent several differential diagnoses, the primary concern was whether his known malignancy had metastasized to the skin.

Given his known malignancy history, which stain would be most useful to highlight the underlying pathology?

A.) Factor XIIIA+

B.) CD21+

C.) CD207+

D.) CD31+

E.) S100+

Correct answer: C.) CD207+

Given the multifocal ulcerations found on exam and pathologic findings of an infiltrate predominantly throughout the dermis and diving deep into the subcutaneous tissue, a malignant process was suspected. The infiltrative cells stained positive for CD207, as well as CD1a and S100. The infiltrate had frequent atypical cells and mitotic figures. As such, the patient was diagnosed with Langerhans cell sarcoma, now with cutaneous metastasis. Langerhans cell sarcoma is a rare neoplastic disorder of Langerhans cells1. According to the Histiocyte Society, there are 5 groups in classifying histiocytoses and neoplasms of the dendritic cell lineages. Langerhans cell sarcoma falls under the malignant, or “M group,” and is a distinct entity from Langerhans cell histiocytosis2. However, Langerhans cell sarcoma will stain positive for typical Langerhans cell markers. These are CD207 (Langerin), CD1a and S100. However, CD207 and CD1a are the most specific stains for Langerhans cells, either of which would have been correct for this question3. Although S100 stain positive for these cells, it also can stain positive for melanocytic proliferations amongst others, so would not be most useful in this case7.

Langerhans cell sarcoma has been diagnosed less than 100 times in the literature1. It can present with both cutaneous and systemic findings, often with multiorgan involvement. There does not appear to be a certain age predilection, as a systematic review in 2015 documented an age range of diagnosis as 11 months to 81 years.1 In this same review, 75% of patients had lymph node involvement, approximately 50% had cutaneous involvement and numerous patients had lung, liver or spleen involvement1. The cutaneous manifestations for this disease process vary from ulcerations to fungating masses, to more indolent appearing nodules. Given its rarity, no consistent presenting cutaneous morphology or lesion is identifiable. The pathogenesis is not well elucidated but is thought to be driven by mutations in the RAS/MAPK/BRAF pathway4. Diagnostic criteria include malignant cytological features such as atypia, hyperchromia and atypia as well as expression of typical Langerhans cell markers as discussed above1. Clear treatment guidelines do not exist, but include surgical excision, radiation, chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation1. Additionally, targeted therapies against PD-1 and BRAF have shown promise in case reports however no large studies have been published looking at the efficacy of these5,6. The prognosis is poor, particularly in metastatic disease but can be favorable if presenting with one site disease1.

Incorrect stains in answer choices7

Factor XIIIA (choice A) – stains dermal dendritic cells, positive in dermatofibroma and negative in DFSP

CD21 (choice B) – follicular dendritic cell marker, highlights residual follicle in lymphoma

CD31 (choice D) – helpful in confirming vascular origin of tumors, more specific than CD34 for vascular processes

S100 (choice E) – stains melanocytes, Langerhans cells, sweat glands, nerves, Schwann cells, myoepithelial cells, fat, muscle and chondrocytes

References

- Langerhans Cell Sarcoma: A Systematic Review.” Cancer Treatment Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Revised Classification of Histiocytoses and Neoplasms of the Macrophage-Dendritic Cell Lineages.” Blood, U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Mizumoto N, Takashima A. CD1a and langerin: acting as more than Langerhans cell markers. J Clin Invest. 2004 Mar;113(5):658-60. doi: 10.1172/JCI21140. PMID: 14991060; PMCID: PMC351325.

- Gounder, Mrinal M, et al. “Trametinib in Histiocytic Sarcoma with an Activating MAP2K1 (MEK1) Mutation.” The New England Journal of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 17 May 2018,

- Zanwar, Saurabh, et al. “Prolonged Remission with Pembrolizumab and Radiation Therapy in a Patient with Multisystem Langerhans Cell Sarcoma.” Haematologica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Sept. 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9425309/.

- C;Tazi A; “Dramatic Transient Improvement of Metastatic BRAF(V600E)-Mutated Langerhans Cell Sarcoma under Treatment with Dabrafenib.” Blood, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26468227/.

- Elston, D. M., Ferringer, T., & Ko, C. J. (2019).Dermatopathology. Elsevier.