April 2024 Case Study

Author: Adam Rosenfeld, MD1

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

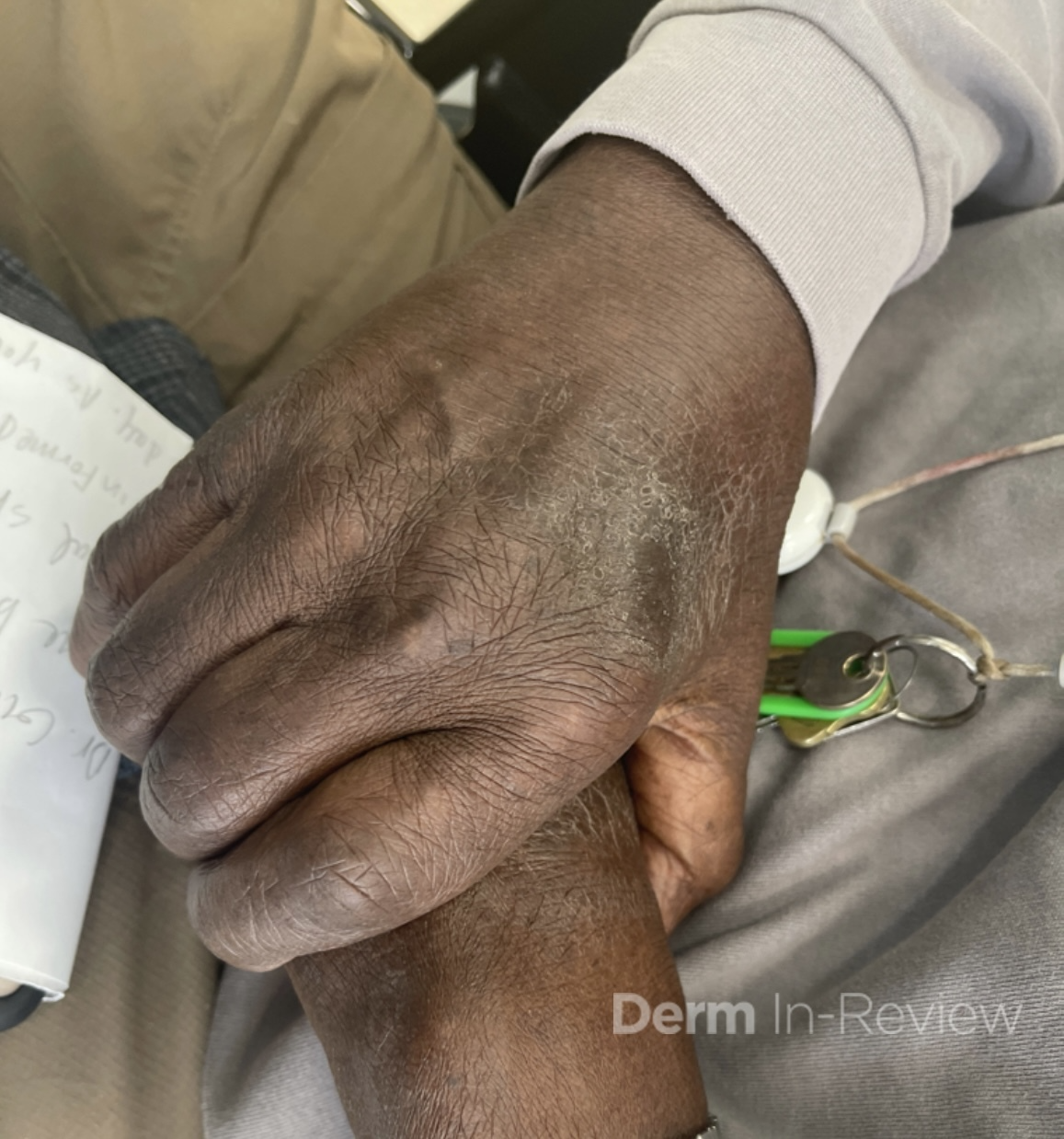

A 79-year-old gentleman presented to the ED with altered mental status. The day prior, his family had found him “confused and weak” which resolved by later that evening. However, the next day, he was “dazed” had difficulty walking, which sparked the presentation to the emergency room. On examination, the patient was found to have an erythematous to violaceous, somewhat reticulated plaque on the posterior neck with a background of mottled, reddish-brown patches (figure 1). On the left hand, he was found to have eroded erythematous papules of the MCPs, PIPs, DIPs and in between the joint spaces (figure 2).

Based on the most likely diagnosis, which of the following would not be a reasonable part of the work up in adult patients?

A.) Pulmonary function tests

B.) CA 19-9

C.) CT chest/abdomen/pelvis

D.) MRI brain

E.) EKG/echocardiogram

Correct Answer: D – MRI Brain

Explanation/Literature review:

Poikiloderma of the neck, with classic “Gottron’s papules” on the left hand, are most concerning for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic multi-system inflammatory condition that is of presumed autoimmune pathogenesis1. It classically presents with a symmetric, proximal, extensor inflammatory myopathy and a characteristic cutaneous eruption. Dermatomyositis has a bimodal age distribution, with both adult and juvenile forms. The pathogenesis is believed to be a result of an immune mediated process triggered by external factors (malignancy, infectious agents) in genetically predisposed individuals1. Additionally, the interferon pathway has recently been implicated as critical in its pathophysiology2. Serum antinuclear autoantibodies are often present which further supports an autoimmune etiology. The cutaneous features include pathognomonic findings of Gottron’s papules (pink to violaceous papules on dorsal hands) and heliotrope eruption (pink-violaceous erythema involving the upper eyelids). Other findings include poikiloderma of the upper back (“shawl” sign) and upper chest, nailfold abnormalities (periungal erythema, dilated capillary nail bed loops) as well as scaly erythema of the lateral thighs (holster sign) and scalp involvement3. In juvenile DM, calcinosis cutis is common, particular on the extensor surfaces1. When evaluating muscle disease, a detailed history assessing proximal muscle groups as well as strength testing should be performed. Cutaneous disease precedes the appearance of myositis by 3-6 months in almost 50% of cases while 10% have myositis prior to any skin findings3. Importantly, DM exists on a spectrum where either skin or muscle phenotype can predominate and can also present as amyopathic. Diagnosis is often made clinically without a skin biopsy however it may be helpful if exam findings are subtle or atypical. Histopathology shows an interface dermatitis with dermal mucin deposition, which would be indistinguishable from lupus erythematosus3. Myositis specific autoantibodies in recent years have been helpful in identifying associated phenotypes. Anti-Mi-2 is associated with both adult and juvenile DM, with milder muscle disease and a good response to treatment1. Anti-MDA5 is associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and cutaneous ulcerations3. Anti-TIF-1 gamma and Anti-NXP-2 are most closely associated with malignancy3. Once DM is diagnosed, additional work up is required including but not limited to serum CK/aldolase, EMG or MRI of muscle, pulmonary function tests (answer choice A), EKG/echocardiogram (answer choice E) and barium swallow or manometry1. Dermatomyositis and its association with malignancy is well known, with a recent study showing the risk to be 6x higher than the general population4. Most common malignancies include ovarian, colon, breast, lung, hematopoietic and nasopharyngeal cancer, particularly in Asian populations5. Although no specific guidelines exist, initial work up includes CBC, CMP and UA as well as chest x-ray and age-appropriates screening. CT chest/abdomen/pelvis (answer choice C) is typically performed if the initial work up is worrisome or in patients that are considered high risk. CA 125 and CA 19-9 (answer choice B) can be considered based on individual patient risk factors. Brain MRI (answer choice D) is not routinely part of the work up as brain neoplasms/malignancies are not strongly associated with DM. Treatment includes skin directed therapy with topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors and photoprotection1. Historically for patients with severe disease, first line therapy included systemic steroids plus disease modifying antirheumatic drugs such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil2. However, IVIG was recently FDA approved for DM and has shown to be very effective regardless of disease severity6. Rituximab or cyclophosphamide are sometimes added, particularly when there is lung or severe muscle involvement7. Apremilast has been shown to help with recalcitrant disease and can be considered as an adjunct treatment8. JAK inhibitors as well as more targeted therapy (anti-IFN antibodies) will likely play a more substantial role in the future 9,.10.

Incorrect answer choices

(choice A) – Pulmonary complications are a well-known cause of morbidity and mortality in dermatomyositis and are a critical part of the work up.

(choice B) – CA19-9 screens for pancreatic cancer and is sometimes indicated as part of the work up based on patient risk factors.

(choice C) – CT chest/abdomen/pelvis is often indicated in adult patients to evaluate for malignancy.

(choice E) – EKG or echocardiogram is performed as conduction defects or other arrhythmias can be seen and do not always present with symptoms.

References

-

- Bolognia, J., Schaffer, J., & Cerroni, L. (2018). Dermatology (Fourth edition.). Philadelphia,Pa: Elsevier.

- Bolko L, Jiang W, Tawara N, Landon-Cardinal O, Anquetil C, Benveniste O, Allenbach Y. The role of interferons type I, II and III in myositis: A review. Brain Pathol. 2021 May;31(3):e12955. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12955. PMID: 34043262; PMCID: PMC8412069.

- Cobos GA, Femia A, Vleugels RA. Dermatomyositis: An Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020 Jun;21(3):339-353. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00502-6. PMID: 32096127.

- Hu T, Vinik O. Dermatomyositis and malignancy. Can Fam Physician. 2019 Jun;65(6):409-411. PMID: 31189628; PMCID: PMC6738379.

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, Fretwell D, Chung L, Callen JP, Fiorentino D. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: Data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jan;97(2):e9639. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009639. PMID: 29480875; PMCID: PMC5943873.

- Werth VP, Aggarwal R, Charles-Schoeman C, Schessl J, Levine T, Kopasz N, Worm M, Bata-Csörgő Z. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) in improving skin symptoms in patients with dermatomyositis: a post-hoc analysis of the ProDERM study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023 Oct 2;64:102234. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102234. PMID: 37799613; PMCID: PMC10550512.

- (n.d.). Retrieved April 10,2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-dermatomyositis-and-polymyositis-in-adults.

- Bitar C, Ninh T, Brag K, Foutouhi S, Radosta S, Meyers J, Baddoo M, Liu D, Stumpf B, Harms PW, Saba NS, Boh E. Apremilast in Recalcitrant Cutaneous Dermatomyositis: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 Dec 1;158(12):1357-1366. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3917. PMID: 36197661; PMCID: PMC9535502.

- Paik JJ, Lubin G, Gromatzky A, Mudd PN Jr, Ponda MP, Christopher-Stine L. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors in dermatomyositis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023 Mar;41(2):348-358. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/hxin6o. Epub 2022 Jun 28. PMID: 35766013; PMCID: PMC10105327.

- Aggarwal, R., Domyslawska, I., Carreira, P., Fiorentino, D., Sluzevich, J., Werth, V., Banerjee, A., Chu, M., Oemar, B., Salganik, M., Sloan, A., Vincent, M., & Peeva, E. (2023, June 1).POS1207 efficacy and safety of ANTI-IFNΒ-SPECIFIC monoclonal antibody, PF-06823859, on myositis: Phase 2 study in patients with moderate-to-severe dermatomyositis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. https://ard.bmj.com/content/82/Suppl_1/936.1.citation-tools

March 2024 Case Study

Authors: Cleo Whiting, BA1, Emily Murphy, MD1, Karl Saardi, MD1

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

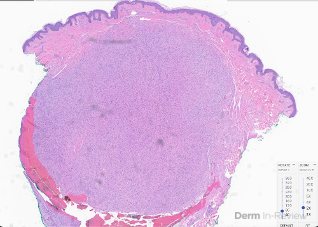

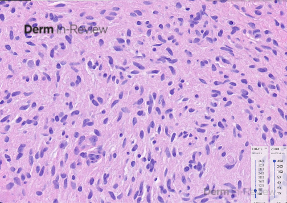

A 57-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension presented with numerous pink to skin-colored, soft, mildly tender papules and nodules on the right posterior shoulder, upper arm, and forearm (figure 1A and 1B) that appeared 15 years ago. She also complained of several deeper and larger growths on the bilateral thighs and left hip that appeared a few years ago. A shave biopsy of one of the papules was performed (figure 2A and 2B, hematoxylin-eosin staining). Immunohistochemistry was positive for S100 and negative for smooth muscle actin. A buccal swab was obtained for sequencing of the NF1 gene and the results were negative for pathogenic mutations.

Based on the clinical presentation and biopsy findings, what risks should the patient be counseled about?

A.) None, reassurance only

B.) Risk of renal cell carcinoma

C.) Risk of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

D.) Potential inheritance of condition by offspring

E.) B & D

F.) C & D

Correct Answer: F

Explanation/Literature review:

Given the segmental distribution of biopsy-confirmed neurofibromas and negative genetic testing, the patient was diagnosed with mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Also referred to as segmental or localized NF1, this condition results from a post-zygotic pathogenic mutation in one copy of the NF1 gene.1 Mosaic NF1 is a rare, heterogeneous disorder characterized by localized cutaneous or neural findings typical of generalized NF1, such as neurofibromas, intertriginous freckling, and multiple, large cafe-au-lait macules.2 The affected NF1 gene encodes for the tumor suppressor protein neurofibromin, a GTPase-activating protein that regulates the RAS-MAPK pathway; biallelic loss of function of NF1 leads to the development of neurofibromas and other NF1-associated tumors.3

There are no specific guidelines for the management of mosaic NF1, although individuals with this condition may experience complications typical of generalized NF1, including the transformation of plexiform neurofibromas to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) (choice C), so reassurance alone is not appropriate (choice A).2,4,5 Although rare, gonadal mosaicism is also possible and offspring of the individual can acquire generalized NF1 (choice D).5 The diagnostic criteria for mosaic NF1 have been recently re-established, and revealing NF1 mutations in affected skin, but not in seemingly unaffected tissues like saliva and blood, is one way to make the diagnosis.6

While individuals with mosaic NF1 have an increased risk of malignancy during their lifetime, renal cell carcinoma is associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer [HLRCC], also known as Reed syndrome,7 and neurofibromatosis type 2 (choice B, E).8 Characterized by cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas, and renal cell carcinoma, HLRCC is caused by a pathogenic mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene and inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance.7

References

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8(6):455-459. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200493

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56(11):1433-1443. doi:10.1212/wnl.56.11.1433

- Maertens O, De Schepper S, Vandesompele J, et al. Molecular dissection of isolated disease features in mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):243-251. doi:10.1086/519562

- Stewart DR, Korf BR, Nathanson KL, Stevenson DA, Yohay K. Care of adults with neurofibromatosis type 1: a clinical practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2018;20(7):671-682. doi:10.1038/gim.2018.28

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(1):9-17. doi:10.1111/pde.12673

- Legius E, Messiaen L, Wolkenstein P, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: an international consensus recommendation. Genet Med. 2021;23(8):1506-1513. doi:10.1038/s41436-021-01170-5

- Scharnitz T, Nakamura M, Koeppe E, et al. The spectrum of clinical and genetic findings in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) with relevance to patient outcomes: a retrospective study from a large academic tertiary referral center. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13(1):236-244. Published 2023 Jan 15.

- Paintal A, Tjota MY, Wang P, et al. NF2-mutated Renal Carcinomas Have Common Morphologic Features Which Overlap With Biphasic Hyalinizing Psammomatous Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Study of 14 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46(5):617-627. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001846

February 2024 Case Study

Authors: Nagasai Adusumilli, MD, MBA1

1. Department of Dermatology, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

A 75-year-old male with a medical history of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, undergoing treatment with multiple systemic therapies, presented with 3 weeks of pink lesions on his hands, feet, and scrotum, with exquisite pain limiting ability to hold a pen and ambulate. Findings on the hands and feet are shown in Figure 1, and scrotal findings are shown in Figure 2. Notably, mucosa of the eyes, nose, mouth, urethral meatus, and anus were not involved. The patient experienced symptomatic improvement with 2 days of high potency topical corticosteroids and topical keratolytics.

Based on the clinical presentation, which of the following categories of medications has been most extensively implicated for this drug reaction?

A.) PD-1 inhibitors

B.) Beta-lactam antibiotics

C.) Aromatic anticonvulsants

D.) Sulfonamides

E.) Multikinase inhibitors

Correct Answer: E.) Multikinase inhibitors

Explanation of Correct Answer:

This patient’s clinical history and findings of multiple tender, pink-red thin macules and patches with a dusky center in the interdigital spaces of the hands, on the palmar surfaces of the fingers, and on the heels of the feet, along with scrotal desquamation, were consistent with hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) and scrotal erythema, secondary to axitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway. HFSR is classically characterized by discrete, exquisitely painful lesions with a halo of erythema, and hyperkeratotic lesions localized to sites of high contact, friction, and pressure, such as tips of fingers and toes, skin overlying metacarpophalangeal or interphalangeal joints, and heels.1,2 HFSR tends to develop within 2-4 weeks of starting multikinase inhibitors, such as sorafenib, sunitinib, cabozantinib, and axitinib (choice E), with pain that can impair range of motion, weight bearing, and overall function.1,2 Although scrotal involvement secondary to multikinase inhibitors is not as common, scrotal erythema, desquamation, and even ulceration have been reported.3

As newer immunotherapies and small molecule inhibitors are increasingly approved for more indications, identifying common and distinct drug reactions is integral to dermatology. Although skin reactions to any medication can be varied and atypical for individual patients, the morphology can be the key to diving deeper into the medical history to pinpoint the culprit, particularly as comorbidities and polypharmacy increase. Adverse skin eruptions from programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors (choice A), such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, more frequently present as morbilliform dermatoses, pruritus, lichenoid eruptions, psoriasiform dermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid.4 Although beta-lactam antibiotics encompass many medications, such as penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams, with a wide range of clinical presentations for drug reactions, the class overall is one of the most common causes of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis5 (choice B). Aromatic anticonvulsants, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital (choice C) are commonly implicated in drug induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), previously drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).5 Similarly, drug reactions from sulfonamides (choice D) have multiple possible presentations, but exanthematous eruption, fixed drug eruption, and SJS/TEN are the most characteristic.5

HFSR is often used interchangeably with palmoplantar erythrodysthesia, or hand-foot syndrome, which was initially described as a subset of toxic erythema of chemotherapies, such as taxanes, cytarabine, capecitabine, anthracyclines, and systemic 5-fluorouracil. Although HFSR can clinically appear similar to hand-foot syndrome, they are separate drug reactions, with the localized hyperkeratotic lesions with a rim of erythema distinct from the symmetric erythema, edema, paresthesia, and dysesthesia seen with hand-foot syndrome from cytotoxic chemotherapies. A high density of eccrine glands is thought to drive the skin manifestations of hand-foot syndrome5 whereas inhibited vascular repair mechanisms in fibroblasts and endothelial cells via VEGF and platelet-derived growth receptor (PDGFR) are hypothesized to predispose areas of trauma to HFSR.6 In fact VEGF and PDGFR inhibitors, such as sorafenib, sunitinib, cabozantinib, and axitinib are among the multikinase inhibitors reported to cause HFSR.1,3,6

Contrary to the nomenclature, the tender erythematous patches and plaques are not limited to just the hands and feet. Flexural surfaces and bony prominences can also be affected. Identifying that each figure of this case illustrates areas of high friction or pressure is key to clinching the diagnosis, even without knowing the specific medications that can treat metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Grading the severity of cutaneous adverse events dictates the overall management strategy.7 Because these symptoms are limiting self-care activities of daily living, this patient has a grade 3 cutaneous adverse event,7 warranting collaboration with oncology colleagues to consider dose reduction, discontinuation, or temporary cessation of the causative anticancer agent.1 In the interim, high potency topical corticosteroids and topical keratolytics, such as urea cream, may provide symptomatic relief.1,8

References:

- Lacouture ME, Wu S, Robert C, at al. Evolving strategies for the management of hand-foot skin reaction associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Oncologist. 2008 Sep;13(9):1001-11. PMID: 18779536.

- Kaul S, Kaffenberger BH, Choi JN, Kwatra SG. Cutaneous adverse reactions of anticancer agents. Dermatol Clin. 2019 Oct;37(4):555-568. PMID: 3146695.

- Zuo RC, Apolo AB, DiGiovanna JJ, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor cabozantinib. JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Feb;151(2):170-7. PMID: 25427282.

- Adusumilli NC, Friedman AJ. Treating cutaneous immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint blockade. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Oct 1;20(10):1133-1134. PMID: 34636526.

- Valeyrie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Chapter 21 – Drug Reactions. In: Dermatology. Fourth Edition. Elsevier; 348-375.

- Fischer A, Wu S, Ho AL, Lacouture ME. The risk of hand-foot skin reaction to axitinib, a novel VEGF inhibitor: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Investigational new drugs. 2013;31(3):787-797. PMID: 23345001.

- NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0 data files. 2017. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html. Accessed 20 Jan 2024.

- Ren Z, Zhu K, Kang H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the prophylactic effect of urea-based cream on sorafenib-associated hand-foot skin reactions in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Mar 10;33(8):894-900. PMID: 25667293.

January 2024 Case Study

Authors: Sapana Desai & Nidhi Shah

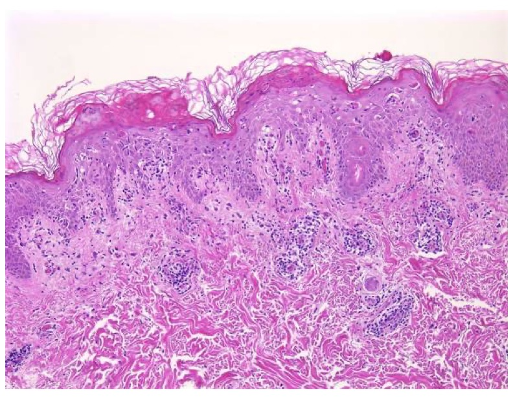

A 29-year-old Caucasian male with history of asthma and atopic dermatitis presents with a multifocal, burning, and pruritic rash that erupted three weeks ago. On physical exam, there are innumerable, erythematous, reddish-brown papules, some with central hemorrhagic crusting spread along the chest, abdomen, and upper extremities, Figure 1. Dermatopathology findings from a subsequent punch biopsy are shown in Figure 2.

Which of the following diagnosis is the patient at an increased risk of developing?

A) Dermatomyositis

B) Postherpetic Neuralgia

C) Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

D) Mucha-Habermann Disease

E) Iron Deficiency Anemia

.

.

Answer: (D) Mucha-Habermann Disease

Explanation of Correct Answer:

This patient’s clinical presentation coupled with a biopsy revealing vacuolar interface dermatitis, lymphocytes in every vacuole, erythrocyte extravasation, keratinocyte necrosis, and superficial and deep perivascular lymphoid infiltrative, is indicative of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA).1

PLEVA is an idiopathic, benign, cutaneous inflammatory dermatosis with increased predilection for the trunk, proximal extremities, and flexural regions. The eruption is polymorphous, as lesions exist in all stages of development, and successive crops of lesions can last from a few weeks to months or even years before resolution.1,2 The disease does not discriminate by race or gender and primarily affects children and young adults, with a slight male predominance. While exact etiology and pathogenesis of PLEVA remains unknown, it is speculated to be an inflammatory reaction triggered by certain infectious agents with pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Group A Streptococcus, and herpes simplex virus type 2, an inflammatory response secondary to T-cell dyscrasia, or an immune complex-mediated hypersensitivity.2 PLEVA may also develop following the use of certain medications including but not limited to atezolizumab, pembrolizumab, and topical diphenylcyclopropenone.1,2,3

Although rare, Mucha-Habermann disease (D) may follow an existing diagnosis of PLEVA or occur de novo.2,3 Patients affected by FUMHD present with necrotic papules that progress to plaques and large coalescent ulcers. Skin ulceration can be extensive and painful, including oral and genital mucosa. Common systemic symptoms include high fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, central nervous system manifestations, joint pain, respiratory complications, and death.1,2,3

Explanation of Incorrect Answers:

Dermatomyositis (A) is an inflammatory myopathy with autoimmune pathogenesis affecting women more commonly than men, with a bimodal peak of incidence between ages 5 and 14 and ages 45 and 65. Clinical presentation classically encompasses a heliotrope rash (periorbital erythema with edema, occasionally involving the cheeks and nose), Holster sign (symmetric poikiloderma of the lateral thighs below the greater trochanter), and V-sign (confluent erythematous patches over the upper central chest and lower anterior neck).3,4 Dermatomyositis is sub-classified into adult-onset disease and juvenile disease (JDM). Serum antinuclear autoantibodies are often present, as are other myositis-specific autoantibodies, which are useful as prognostic indicators while aiding in diagnosis and management of disease. Dermatomyositis is related to and possibly results from an immune-mediated process triggered by outside factors like drugs, infectious agents, and malignancy in individuals with genetic predisposition.4

Postherpetic neuralgia (B) is regarded as the most common long-term complication of reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), also known as shingles.3,5 VZV is characterized by prodrome of pain/burning followed by the onset of a rash by 7 to 10 days. The distinctive rash presents as crops of erythematous vesicles that evolve into pustules and crusts, often in a dermatomal distribution. The hallmark clinical manifestation of postherpetic neuralgia is a lancinating/burning pain in a unilateral dermatomal pattern that persists for three or more months after the onset of a herpes zoster outbreak.5 Well-established risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia include age, severe immunosuppression, the presence of a prodromal phase, allodynia, ophthalmic involvement, and diabetes mellitus.3,5 Although treatment for postherpetic neuralgia is challenging, traditional non-invasive first-line therapeutic approaches include oral and topical medications, such as gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, and lidocaine 5% patch.3

Sweet syndrome is associated with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (C), a myeloproliferative disorder. Sweet syndrome, or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare cutaneous disorder characterized by the abrupt development of painful, tender, erythematous plaques or nodules, fever greater than 38*C, and a nodular perivascular neutrophilic dermal infiltrate without evidence of vasculitis on histologic examination.6,7 Sweet syndrome may occur before, at the time of or after the diagnosis of malignancy. When associated with malignancy, it is more likely to be associated with older age of onset and cytopenia, and accounts for 15-20% of total cases of Sweet syndrome.6 While the exact pathogenesis of Sweet syndrome is elusive, genetic factors such as HLA-B54, MEFV gene mutations, and chromosome 3q abnormalities have shown to be contributory.6,7

Iron Deficiency Anemia (E) may be associated with Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome [BRBNS/ Bean’s Syndrome]. Patients have characteristic cutaneous findings of multiple blue to violaceous soft and compressible nodules on the skin or mucous membranes that present at birth or in early childhood and develop numerous venous malformations involving the skin and gastrointestinal tract over their’ lifetime.8,9 Typical lesions range in size from a few millimeters to up to 4 centimeters in diameter, are rubbery in consistency, and gradually evolve with time eliciting pain most prevalent at night.8 Uniquely, lesions swell in gravity-dependent positions, and patients exhibit focal areas of hyperhidrosis overlying these lesions. Although most cases of BRBNS are sporadic, autosomal dominant inheritance has been suggested, as well as studies reporting stem cell factor/c-kit signaling systems contributing to vascular overgrowth. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common symptom ranging from obscure to massive bleeding leading to severe iron deficiency anemia. Other rare complications may include perforation, intussusception, intestinal torsion, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and thrombocytopenia.8,9

References

- Pereira, N., Brinca, A., Brites, M., Juliao, M. Tellechea, O., Goncalo, M. Pityraisis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Dermatol. March 2012; 4(1): 61-65.

- Teklehaimanot, F., Gade, A., Rubenstein, R. Pityriasis Lichenoides Et Varioliformis Acuta (PLEVA). StatPearls. 2023.

- Bolognia, J., Schaffer, J., & Cerroni, L. (2018). Dermatology (Fourth edition.). Philadelphia,Pa: Elsevier. of clinical medicine. Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32516921/

- DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 Feb 1;82(2):267-81.

- Gruver, C., Guthmiller, K. Postherpetic Neuralagia. 2023.

- Guarneri, C., Wollina, U., Lotti, T., Maximov, G., Lozev, I., Gianfaldoni, S., Pidakev, I., Lotti, J., Tchernev, G. Sweet’s Syndrome (SS) in the Course of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Open Access Maced Journal Medical Sciences. January 2018; 6(1): 105-107.

- Vashisht, P., Goyal, A., Holmes, M. Sweet Syndrome. 2023.

- Moghadam, A., Bagheri, M., Eslami, P., Farokhi, E., Asl, A., Khavaran, K., Iravani, S., Saeedi, S., Mehrvar, A., Dooghaie-Moghadam, M. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome because of 12 Years of Iron Deficiency Anemia in a Patient by Double Balloon Enteroscopy; A Case Report and Review of Literature. Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2021; 13(2): 153-159.

- Hu, Z, Lin, X., Zhong, J., He, Qingfang., Peng, Q., Xiao, J., Chen, B., Zheng, J. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome with the Complication of Intussusception: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020; 99(28).

December 2023 Case Study

Adam Rosenfeld, MD1

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

A 46-year-old male with reported history of atopic dermatitis presented to the ED with a 2–3 month history of a diffuse skin eruption as well as multiple growths on his forehead. Review of systems was notable for fatigue and chills. Patient endorsed unintentional weight loss and multiple episodes of night sweats throughout this time frame. On examination, the patient was erythrodermic with diffuse hyperpigmented and erythematous scaly plaques as well as multifocal, somewhat necrotic appearing nodules on the right forehead/temple area (figures 1,2). A punch biopsy demonstrated a superficial to deep dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells with limited epidermal involvement.

Given the overall presentation, loss of what T-cell marker would be most consistent with the likely diagnosis?

A.) CD20

B.) CD3

C.) CD4

D.) CD7

E.) CD45

.

.

Correct Answer: D

Explanation/Literature review:

Erythroderma and multifocal nodules in the context of unintentional weight loss and constitutional symptoms, are most concerning for Sezary syndrome, which classically demonstrates aberrant loss of CD71. Sezary Syndrome is an aggressive subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that has been defined by erythroderma, superficial lymphadenopathy, and atypical T-cells in the blood1. Mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common form of CTCL, where disease is typically skin limited, patients often have a much more indolent presentation. Sezary patients on the other hand, present much more acutely and have a poorer prognosis3. The erythroderma in these patients is intensely pruritic1. Patients can also demonstrate diffuse alopecia, keratoderma, eyelid edema and dystrophic nails1. Mycosis fungoides can be difficult to diagnosis and often requires multiple skin biopsies and can mimic atopic dermatitis (AD). Our patient had a known diagnosis of AD, so it is difficult to know if this was CTCL that simply hadn’t been diagnosed yet. The prior school of thought indicated that mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome were on a spectrum, where Sezary was progression of a patient’s known disease1. However, while the progenitor cells in MF and Sezary both stem from memory T-cells, in MF they are considered skin resident as opposed to central resident memory T-cells in Sezary2.

Histologic findings can range from superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, eosinophilic dermatitis with or without spongiosis, to a lichenoid infiltrate. Pautrier micro-abscesses (collections of atypical lymphocytes within the epidermis) and epidermotrophism (lymphocytes moving from the dermis into the epidermis) can also be seen3,4. Given the variability and often subtilty of histologic findings, the staining pattern is most diagnostic. The infiltrate will be CD3+ and CD4+ (answer choices B and C) but will show aberrant loss of CD7, a marker of immature T-lymphocytes (answer choice D)1. CD20 and BCL2 (answer choice A and E) would be helpful in diagnosing a B-cell lymphoma but would not be relevant in this case4. Although skin involvement is supportive of the diagnosis, to meet criteria for Sezary syndrome, patients most have an atypical, clonal T-cell proliferation within the blood. This can be identified with flow cytometry as well as T-cell rearrangement studies. The population of T-cells must have one of the following: (1) CD4+/CD8+ ratio of >10 (2) CD4+CD7- >40% or CD4+CD26- >301. Further work up includes but is not limited to CBC, CMP, peripheral blood smear and LDH, which can have prognostic importance1. Imaging is indicated to assess for lymphadenopathy as well as visceral involvement (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly)1. Importantly, Sezary patients are inherently immunosuppressed given the abnormal T-cell population as well as barrier dysfunction as it relates to erythroderma2. Sezary syndrome is deemed stage IV from skin involvement but based on lymph node and visceral involvement, more exact staging is done to best guide treatment options, with the help of our oncology colleagues5. Skin directed therapy includes topical or systemic steroids as well as phototherapy or electron beam radiation. Given blood involvement in Sezary syndrome, treatment is typically systemic1. For patients without visceral involvement, therapeutic options include extracorporeal photopheresis, oral retinoids (Bexarotene, Acitretin), interferons or histone deacetylase inhibitors (Vorinostat, Romidespin)1. Some of the targeted therapies include Brentuximab (monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody), mogamulizumab (CCR4 chemokine antibody) as well as Alemtuzumab (monoclonal anti-CD 52 antibody)1. Stem cell transplant is considered the only potentially curative option1.

Incorrect stains in answer choices3

CD20 (choice A) – B-cell antigen. Positive in B-cell lymphomas and negative in T-cell lymphomas. Target for Rituximab.

CD3 (choice B) – Pan T-cell marker. Positive in T-cell lymphomas but negative in B-cell lymphomas

CD4 (choice C) – T-helper lymphocyte marker.

BCL2 (choice E) – An oncogene that inhibits apoptosis. Use in differential diagnosis of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.

References:

- Sezary syndrome – statpearls – NCBI bookshelf. (n.d.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499874/

- Miyashiro D, Souza BCE, Torrealba MP, Manfrere KCG, Sato MN, Sanches JA. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in the Pathogenesis of Sézary Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 15;23(2):936. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020936. PMID: 35055124; PMCID: PMC8781892.

- Elston, D. M. (2019). Dermatopathology. Elsevier.

- Sézary syndrome. Pathology Outlines – Sézary syndrome. (n.d.). https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphomanonBsezary.html

- Olsen EA, Whittaker S, Kim YH, Duvic M, Prince HM, Lessin SR, Wood GS, Willemze R, Demierre MF, Pimpinelli N, Bernengo MG, Ortiz-Romero PL, Bagot M, Estrach T, Guitart J, Knobler R, Sanches JA, Iwatsuki K, Sugaya M, Dummer R, Pittelkow M, Hoppe R, Parker S, Geskin L, Pinter-Brown L, Girardi M, Burg G, Ranki A, Vermeer M, Horwitz S, Heald P, Rosen S, Cerroni L, Dreno B, Vonderheid EC; International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas; United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium; Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Clinical end points and response criteria in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a consensus statement of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 20;29(18):2598-607. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0630. Epub 2011 May 16. PMID: 21576639; PMCID: PMC3422534.

November 2023 Case Study

Author: Alexis E. Carrington, MD

Reviewed by Karl Saardi, MD

A 30 year old female with a history of ulcerative colitis on ustekinumab and prednisone presents to the hospital with a sudden pustular eruption on the face, chest and arms. She also reports painful ulcers and sores on the tongue, lips and gums. Exam shows scattered pustules and tense vesicles with surrounding erythema on the face, upper trunk and arms (Image 1). There are also punched out ulcerations with a white-yellow base on the mucosal lip and gingiva. Labs are significant for ALT and AST elevated to 1847 units/L and 1163 units/L, respectively.

Which of the following next steps will help with diagnosis?

A.) Obtain an HSV/VZV PCR swab

B.) Obtain an enterovirus PCR swab

C.) Obtain a bacterial culture swab

D.) Obtain a fungal culture swab

This patient has disseminated herpesvirus infection complicated by fulminant hepatitis. This was ascertained by a negative HSV IgG 1 and 2 as well as positive HSV2 PCR from cutaneous swab and blood PCR. There was also a component of an acneiform eruption due to chronic steroid use, resulting in a pustular eruption. Her skin findings and hepatitis improved with initiation of IV acyclovir.

Disseminated HSV is a potentially fatal infection that can have visceral involvement. Organs that can be involved include the liver (HSV hepatitis), the central nervous system (meningoencephalitis), lungs (pneumonitis), bone marrow (neutropenia or thrombocytopenia) or the GI tract (necrotizing enterocolitis).1-3 Disseminated HSV is more common in immunocompromised patients, however can occur in immunocompetent patients. In fact, HSV hepatitis should be considered in the setting of acute fulminant liver failure of unknown etiology, as was the case in this patient.4

An HSV/VZV cutaneous swab for PCR (Answer A) is sensitive and specific for detecting herpesvirus infection, which classically presents as painful tense vesicles and punched out mucosal ulcerations and can cause fulminant hepatitis as a sequelae. Swabs for HSV culture are less sensitive but are needed if testing for acyclovir resistance is required. Coxsackievirus, bacterial and fungal etiologies are less likely to cause this cutaneous and systemic presentation (Answers B-D).

References:

- Bolognia, Jean L. Dermatology volume 2. Mosby, 2018.

- Srinivasan D, Kaul CM, Buttar AB, Nottingham FI, Greene JB. Disseminated Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2) as a Cause of Viral Hepatitis in an Immunocompetent Host. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Aug 3;22:e932474. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.932474. PMID: 34341324; PMCID: PMC8349572.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Nov;57(5):737-63; quiz 764-6. PubMed ID: 17939933

- Wei E, Song P, Tan B, Burgin S, Prasad P. Disseminated herpes simplex virus in adult. In: Goldsmith LA, ed. VisualDx. Rochester, NY: VisualDx; 2023. URL:https://www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52676. Accessed October 15, 2023.

October 2023 Case Study

Author: Alexis E. Carrington, MD

Reviewed by Karl Saardi, MD

A 94 year old male with a medical history of CKD aphasia related a stroke presents to the clinic for a rash on the hands, face and abdomen. History of the rash is significantly limited due to his aphasia. Chart review showed that he was prescribed fluocinonide ointment for suspected atopic dermatitis with no improvement. The patient lives in a skilled nursing facility. Labs showed chronic normocytic anemia with normal folate and B12 levels and chronically elevated transaminases with AST 156 and ALT 193. On exam, there are lichenified hyperpigmented scaly plaques that are slightly photo distributed. Facial features suggestive of leonine facies. (Images 1-3).

Which of the following next steps will help diagnose the rash?

A.) Obtain serum Zinc level

B.) Obtain serum Vitamin C level

C.) Obtain flow cytometry

D.) Obtain serum Niacin levels

E.) Obtaining a mineral prep

Correct Answer: D.) Obtain serum Niacin levels

Explanation of Correct Answer:

Pellagra is a potentially fatal disease due to a lack of the vitamin niacin (B3) or its precursor tryptophan. Risk factors include poverty, a diet poor not fortified with niacin (such as maize), alcoholism, carcinoid syndrome and drugs such as isoniazid and azathioprine.1,2The rash is typically a symmetrical photo-distributed rash with a thick scale likened to shellac.

Cheilitis and glossitis are commonly associated with pellagra, as well as other vitamin deficiencies. Dementia and diarrhea are other commonly associated symptoms, completing the “4 Ds” of Pellagra (Dementia, Diarrhea, Dermatitis and Death).2 The World Health Organization recommends treatment of pellagra with Nicotinamide 300 mg by mouth divided 2-3 times daily for 3-4 weeks.4 Repletion with a daily multivitamin can be done to treat for other suspected concomitant vitamin deficiencies.

Answer D is correct to confirm a diagnosis of Pellagra. Acrodermatitis enteropathica due to Zinc deficiency commonly involves the peri-oral, acral and intertriginous areas. (Answer A). Vitamin C deficiency can present as perifollicular purpura, gingival bleeding and corkscrew hair (Answer B). Answer C is to evaluate for Sezary syndrome, which can present with leonine facies, however the plaques and tumoral lesions are typically in photo protected areas. Finally a mineral prep would evaluate for scabies, which less likely involves the face and scalp (Answer E). The rest of the answers are reasonable next steps to narrow down the differential diagnosis; however the photo distribution is a typical finding in pellagra.

References

- Bolognia, Jean L. Dermatology volume 2. Mosby, 2018.

- Hegyi J, Schwartz RA, Hegyi V. Pellagra: dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Jan;43(1):1-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01959.x. PMID: 14693013.

- World Health Organization. Pellagra and its prevention and control in major emergencies. 2000

September 2023 Case Study

by Sapana Desai, MD & Adam Rosenfeld, MD

A 63-year-old woman with history of Hashimoto’s disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and deep venous thrombosis presents with a progressive, multifocal, “rash” involving the extremities including the thighs and buttocks for four-to-five years. Lesions gradually advanced to affecting flexural aspects of the inguinal folds, abdomen, inframammary folds, and axillae. More recently, the patient recognized significant worsening and complains of severe pruritus, pain, and generalized discomfort. Physical examination findings are shown in Figure 1.

Which of the following diagnosis is the patient at an increased risk of developing?

A) Scleromyxedema

B) Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis

C) Vulvular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

D) Pheochromocytoma

E) Dermatomyositis

Correct Answer: (C) Vulvular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Explanation of Correct Answer:

This patient’s clinical presentation, which includes multiple white atrophic plaques comprised of several flat-topped coalescing papules with maceration and scale crust, and a subsequent 4mm punch biopsy revealing a compact stratum corneum, atrophic epidermal with effaced rete, a band-like infiltrate, and associated dermal edema is indicative of extragenital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus (LSetA) with vulvovaginal involvement.

LSetA is an underdiagnosed, chronic, inflammatory mucocutaneous autoimmune dermatosis with increased predilection for the anogenital sites (80% -to- 98%), but can also arise simultaneously in extragenital sites in 15% to 20% of patients- favoring the upper trunk and proximal limbs. Postmenopausal women are predominantly affected and, to a lesser extent, men, prepubertal children, and adolescents, with female-to-male ratios varying between 6:1 and 10:1.1-3 While exact etiology and pathogenesis of LSetA remains elusive, underlying genetics and family predisposition are contributory in 10% of all cases; immunological changes involving increased levels of Th1-specific cytokines, dense T cell infiltration, enhanced BIC/miR expression, as well as autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1 and BP180 antigen also play integral roles. LSetA is characterized by skin atrophy and hypopigmentation, and most commonly incites clinical manifestations of severe pruritus, pain, burning, and sexual dysfunction.2,3 Its relapsing and cumbersome nature warrants every case of LSetA to be treated and managed early, as disease evolvement can lead to scarring and loss of genital anatomical architecture. Furthermore, vulvular lichen sclerosus may evolve to Vulvular Squamous Cell Carcinoma (C) in affected areas with an estimated 5% lifetime risk; however, its association with penile squamous cell carcinoma is not clear.1,3

It is imperative to note that squamous cell carcinoma develops in connection with genital, not extragenital LSetA. Literature suggests that p53 oncogenes, chronic inflammation and oxidative DNA damage are responsible for such malignant transformations. Nonetheless, the risks are significantly decreased by long-term maintenance treatment including an array of topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and well as systemic regimens for refractory cases.1,3

Explanation of Incorrect Answers:

Scleromyxedema (A) is a rare chronic cutaneous mucinosis of unknown etiology, often exhibiting association with rheumatologic diseases and monoclonal gammopathy (IgG-lambda). The disease affects adults between 30 -to- 70 years of age, with no gender predilection. Patients experience widespread symmetric eruptions of waxy, firm erythematous papules measuring 2 -to- 3cm diameter which can present close grouping in a linear distribution.1,4 Gradually, papules evolve to hardened plaques, showing marked sclerosis. In addition to cutaneous changes, 90% of patients experience plasma cell dyscrasia, in conjunction with multisystemic manifestations that may involve cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, respiratory, skeletal, muscular, renal, and nervous systems, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Histologically, scleromyxedema is characterized by excessive dermal mucin deposition, fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; still, histological findings in more than 20% of afflicted patients differs from the classic triad showing lesions that resemble interstitial granuloma annulare.4 Scleromyxedema is an unpredictable, progressive, and debilitating disease, and its relative rarity and elusive pathophysiology has precluded consensus on any one optimal treatment regimens. Even so, current literature supports aggressive treatment with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) is promising while inciting the least number of side effects.

Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis (B) is an infrequent dermatosis that most commonly affects females, and is typically seen in the setting of rheumatic diseases [e.g. rheumatoid arthritis], but also hematological disorders, internal malignancies, infections, and antihypertensive drugs.5 Clinically, the disease is characterized by multiple erythematous papules and plaques, often with annular configuration, predominantly involving inner aspects of the limbs, lateral trunk, and intertriginous sites.5,6 The presence of cord-like indurated lesions (“rope sign”) is often considered pathognomonic. Uniquely, the histopathological examination defines the diagnosis, with presentation of dense and diffuse interstitial infiltrates within the reticular dermis- composed of histocytes in a palisade arrangement and sometimes with necrobiosis of collagen, and deposition of mucin with absence of both vasculitis and neutrophilia.1,5,6

Pheochromocytoma (D) may be associated with neurofibromatosis type 1- an autosomal dominant inherited neurocutaneous disorder due to mutations in NF1 gene on 17q11.2. Pheochromocytoma is a rare neuroendocrine catecholamine-producing tumor of the adrenal medulla that synthesizes and stores excessive amounts of norepinephrine and epinephrine, which when released can evoke life-threatening cardiovascular complications.8 It may be classified as sporadic or familial, with the latter accounting for 10% of all pheochromocytoma cases, and exhibits strong association with hereditary inheritance of multiple endocrine neoplasia IIA and IIB, neurofibromatosis type 1, tuberous sclerosis, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, Sturge-Weber syndrome, and simple familial pheochromocytoma.8,9 Up to 40% of pheochromocytomas are associated with known genetic mutations, with the most common encompassing NF-1 gene, RET proto-oncogene, VHL gene, and genes encoding succinate dehydrogenase subunits.8,9

Dermatomyositis (E) is an inflammatory myopathy with autoimmune pathogenesis affecting women more commonly than men, with a bimodal peak of incidence between ages 5 and 14 and ages 45 and 65. Clinical presentation classically encompasses a heliotrope rash (periorbital erythema with edema, occasionally involving the cheeks and nose), Holster sign (symmetric poikiloderma of the lateral thighs below the greater trochanter), and V-sign (confluent erythematous patches over the upper central chest and lower anterior neck).1,7 Dermatomyositis is sub-classified into adult-onset disease and juvenile disease (JDM). Serum antinuclear autoantibodies are often present, as are other myositis-specific autoantibodies, which are useful as prognostic indicators while aiding in diagnosis and management of disease. Dermatomyositis is related to and possibly results from an immune-mediated process triggered by outside factors like drugs, infectious agents, and malignancy in individuals with genetic predisposition.7

References

- Bolognia, J., Schaffer, J., & Cerroni, L. (2018). Dermatology (Fourth edition.). Philadelphia,Pa: Elsevier. of clinical medicine. Retrieved August 11, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32516921/

- Elston, D. M. (2019). Dermatopathology. Elsevier.

- Krapf JM, Mitchell L, Holton MA, Goldstein AT. Vulvar lichen Sclerosus: current perspectives. Int J Women’s Health. (2020) 12:11–20. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S191200

- Koronowska, S., Osmola-Mankowska, A., Jakubowicz, O., Zaba, R. Scleromyxedema: a rare disorder and its treatment difficulties. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postepy Dermatol Alergol. (April 2013); 30(2): 122-126.

- Veronez, I., Luiz Dantas, F., Valente, N., Kakizaki, P., Yasuda, T., Cunha, Thais. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: rare cutaneous manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Anais Brasileiros De Dermatologia. (May 2015); 90(3): 391-393

- Coutinho, I., Pereira, N., Gouveia, M., Cardoso, J., Tellechea, O. Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis: A Clinicopathological Study. The American Journal of Dermatopathology. (August 2015)); 37(8): 614-619.

- DeWane ME, Waldman R, Lu J. Dermatomyositis: clinical features and pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 Feb 1;82(2):267-81.

- Zografos, G., Vasiliadis, G., Zagouri, F., Aggeli, C., Korkolis, D., Vogiaki, S., Pagoni, M., Kaltsas, G., Piaditis, G. Pheochromocytoma Associated with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Concepts and Current Trends. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2010; 8(14).

- Naranjo, J., Dodd, S. MD, Martin, Y. MD. Perioperative Management of Pheochromocytoma. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2017; 31(4): 1427-1439.