November 2024 Case Study

Authors: Sapana Desai & Dillon Nussbaum

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Patient History

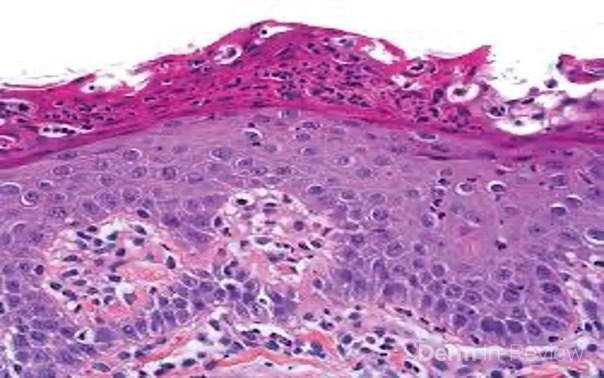

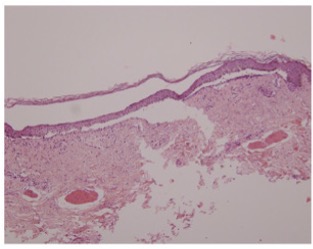

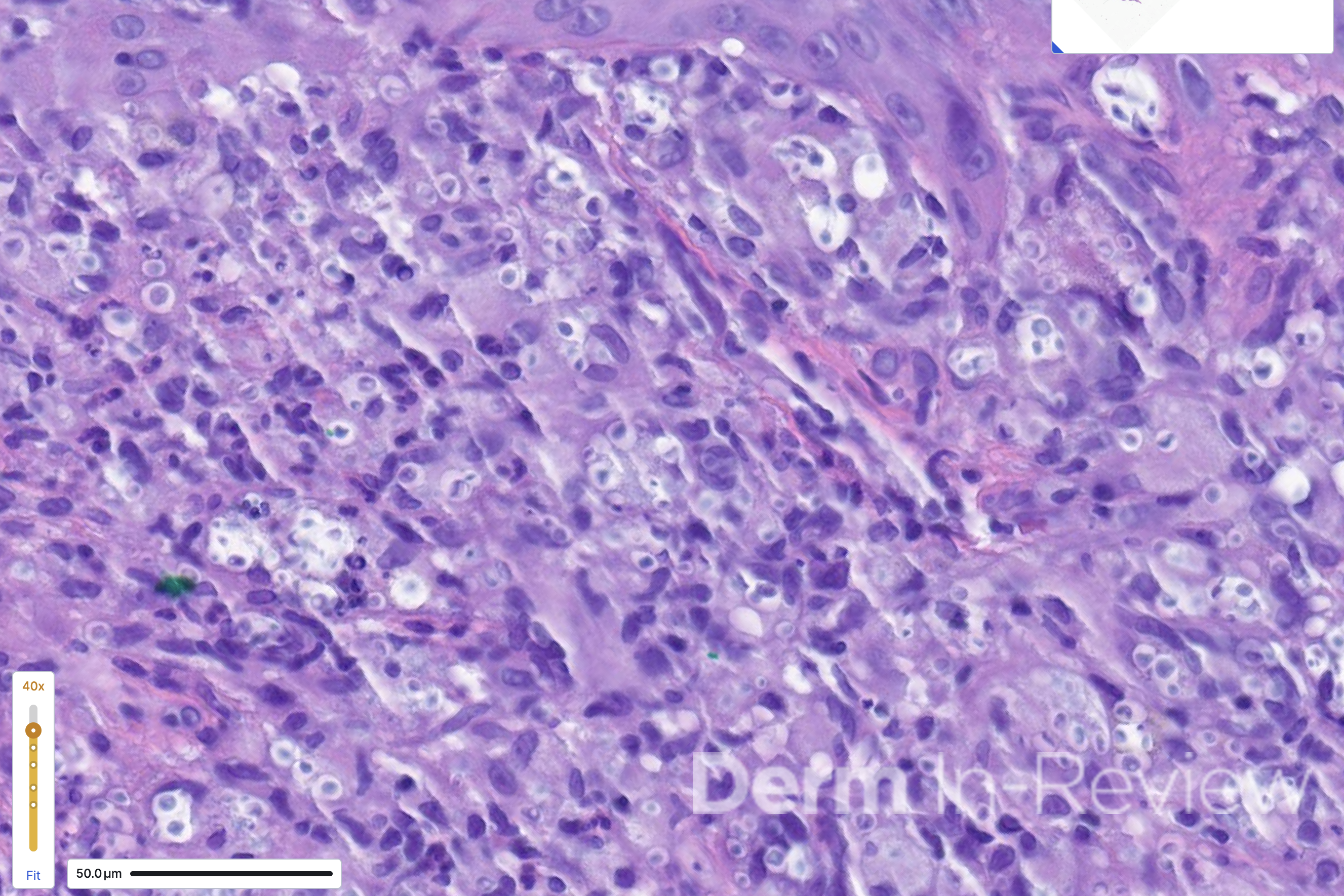

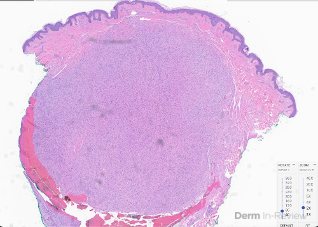

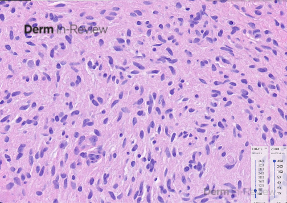

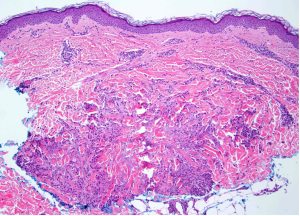

A 65-year-old female with a history of hypertension presents for an intermittently pruritic rash for 11 years that has been unresponsive to topical steroids. On physical examination, there are extensive, well-demarcated, tan to dark brown, erythematous, indurated papules and annular plaques on the abdomen, arms, and lower extremities bilaterally (Figure 1). A punch biopsy was performed (Figure 2, hemoxylin and eosin stain). A colloidal iron stain revealed significant mucin deposition.

Based on the clinical presentation and biopsy findings, what is the next best step in management?

A) Order an antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

B) Perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation

C) Recommend age-appropriate cancer screenings

D) Perform a Wood’s lamp examination

E) Perform repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence

Correct Answer: C

Explanation/Literature Review

Explanation of Correct Answer:

Given the clinical description and associated pathologic finding of palisading necrobiotic granulomas with mucin deposition, the patient was diagnosed with generalized granuloma annulare (GGA).1-4 GGA is a variant of granuloma annulare (GA) characterized by more than 10 red to brown, raised, ring shaped dermal plaques, usually in a symmetric distribution.2,3 GGA is the more extensive variant of GA, which is a benign and often self-limited granulomatous dermatosis that on pathology exhibits dermal necrobiosis, mucin deposition, and palisading or interstitial granulomas. GA can present in five subtypes:

1) Localized GA- represents approximately 75% of all reported cases and presents as well-defined, annular plaques with a circinate configuration, most commonly on the hands and feet;

2) Generalized GA- GGA presents with more than 10 erythematous papules in an annular or arcuate configuration on the trunk and extremities;

3) Subcutaneous GA- presents with deep, firm nodules that resemble pseudo-rheumatoid nodules, most commonly found on the extremities, and seen almost exclusively in children;

4) Patch GA- presents with erythematous, often scaly patches that involve large areas of skin, most commonly on the trunk;

5) Perforating GA- presents with umbilicated papules confined to the trunk and extremities, which subsequently rupture.1-4

The etiology and pathogenesis of GA is largely unknown, but GA has been associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and thyroid disease. The prevalence of GA is estimated to be between 0.1% to 0.4%, and the disease can affect individuals of any age, with an increased predilection for women. Although GA can resolve spontaneously, affected areas tend to recur in many patients.

While rare, GGA can present in association with various malignancies, including blood, breast, cervical, lung, prostate, stomach, and ovarian cancer. Therefore, the best next step for patients with GGA is to C) recommend age-appropriate cancer screenings, especially in the context of elderly patients, atypical or widespread presentations, and recalcitrant disease.4 The most common malignancy associated with GGA is chronic lymphocytic leukemia and the most common solid organ malignancy is prostate cancer. Malignancy associated GA is most commonly seen in the 7th decade, whereas localized GA occurs in younger patients more commonly and malignancy associated GA typically resolves after treatment of the associated cancer.3,4

Explanation of Incorrect Answers:

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease affecting women more commonly than men, with a bimodal peak of incidence between ages 5 and 14 and ages 45 and 65.5,6 DM is sub-classified into adult-onset disease and juvenile disease (JDM). Serum antinuclear autoantibodies are often present, as are other myositis-specific autoantibodies, and ordering antinuclear antibodies (ANA) may be a useful prognostic indicator in diagnosis and management of DM.6

Tinea corporis is a superficial fungal skin infection most commonly caused by trichophyton rubrum, often arising due to factors like excessive heat and humidity, tight clothing, and compromised immunity. Tinea corporis can have a similar annular morphology to GA and should be considered in the differential.7 Tinea corporis typically has a significantly shorter history of several weeks, rather than years, and often demonstrates scale along the advancing border, a feature generally absent in GA. Performing a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation (Answer B) is a helpful tool to rule out a fungal etiology, particularly in scaly lesions where fungal species would exhibit septate hyphae under microscopy.7

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune condition of melanocytes, resulting in depigmentation that on histology exhibits decreased or complete loss of melanocytes, 9 Diagnosis of vitiligo is supported by performing a D) Wood’s lamp examination, which reveals with a peak wavelength of 365nm reveals depigmented areas and helps differentiate vitiligo from other hypopigmentation disorders. Patients with vitiligo can also have other autoimmune diseases, most commonly Hashimoto’s disease.

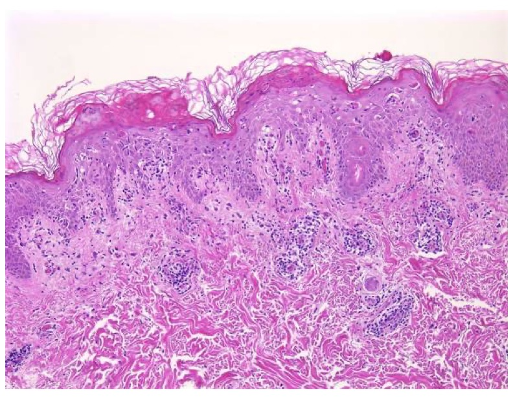

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a chronic vesiculobullous eruption involving antibodies targeting transmembrane proteins. BP manifests as tense bullae on non-mucosal sites, and on pathology reveals subepidermal blisters with eosinophils. BP usually begins with urticarial plaques which tend to have eosinophilic spongiosis on histology. Direct immunofluorescence of BP consists of linear IgG and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction (Answer E). The morphology and presentation of this patient’s rash are not consistent with BP.

References

- Bagci B, Karakas C, Kaur H, Smoller BR. Histopathologic Aspects of Malignancy-Associated Granuloma Annulare: A Single Institution Experience. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2023;10(1):95-103. Published 2023 Mar 4. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology10010015

- Joshi, T., Duvic, M. Granuloma Annulare: An Updated Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment Options. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. January 2022; 23(1): 37-50.

- Piette, E., Rosenbach, M. Granuloma Annulare: Clinical and Histologic Variants, Epidemiology, and Genetics. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology. September 2016; 75(3): 457-465.

- Gittler J., Mir, A., Meehan, S., Pomeranz, M. Photodistributed Granuloma Annulare. Dermatology Online Journal. December 2025; 21(12): 13030.

- O’Connell, K., LaChance, A. Dermatomyositis. New England Journal of Medicine. June 2021; 384(25): 2437.

- Sugie, K. Dermatomyositis. Brain Nerve. May 2024; 76(5): 635-645.

- Chong, AH., Kovitwanichkanont, T. Superficial Fungal Infections. Australian Journal of General Practice. October 2019; 48(10): 706-711.

- Dahir, AM., Thomsen, SF. Comorbidities in Vitiligo: Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Dermatology. 2018; 57(10): 1157-1164.

- Rork JF, Rashighi M, Harris JE. Understanding autoimmunity of vitiligo and alopecia areata. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(4):463-469.

- Image source: The Full Spectrum of Dermatology: A Diverse and Inclusive Atlas