June 2024 Case Study

Author: Nagasai Adusumilli, MD, MBA1

- Department of Dermatology, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Patient History

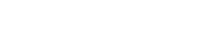

A 60-year-old male with a medical history of HIV (updated CD4 count of 30) presented to the emergency department with headaches, disorientation, and acute onset vision loss. He was found to have an increasing number of skin lesions on the face for the past 3 weeks. Multiple well-demarcated, eroded papulonodules were seen on the nose and forehead (Figure 1). A punch biopsy of the dorsal nose showed the findings on hematoxylin and eosin in Figure 2.

Based on the clinical presentation and biopsy findings, which three stains would be most useful to highlight the underlying pathology?

A.) Verhoeff-Van Gieson

B.) Thioflavin T

C.) Periodic acid-Schiff

D.) Von Kossa

E.) Fontana- Masson

F.) Masson trichrome

G.) Toluidine blue

H.) Mucicarmine

I.) Fite

J.) HHV-8

Correct Answer: C, E, H

Explanation/Literature review:

In the setting of AIDS (CD4 count less than 50), the scattered, umbilicated, and eroded papules and nodules across the head and neck distribution (Figure 1) are suspicious for opportunistic infections. Even within just the infectious category, the differential diagnoses are broad, including molluscum, tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, monkeypox, cat scratch, secondary syphilis, and various mycoses. Histoplasma, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, and Talaromyces are among the deep fungal infections that fit this clinical morphology.1 Figure 2 shows a dermal infiltrate on high power, with innumerable fungal yeasts of different sizes within clear spaces of circular capsules. Yeasts of variable size and shape clustered within capsules are distinctly characteristic of Cryptococcus, particularly in the context of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms and molluscoid cutaneous findings.2 Consequently, a fungal stain like PAS (answer choice C) can help highlight the yeasts.2 Although Fontana-Masson is typically used to highlight melanin and the absence of melanin in vitiligo, the pleomorphic cryptococcal yeasts stain yellow-brown to black with Fontana-Masson (answer choice E).2,3 Mucicarmine (answer choice H) stains pink the organism’s classic polysaccharide capsule,2 which serves as the antiphagocytic virulence factor.

Cryptococcus is an encapsulated fungus found in bird droppings, with human transmission occurring through inhalation of the yeasts.4 The fungus then lies dormant in the hilar lymph nodes and lungs, walled off with granulomatous inflammation.4 During periods of immunocompromise, the fungus proliferates and disseminates throughout the body, including to the brain, bone, and skin.4 Cryptococcus demonstrates a tropism for the skin and brain,5,6 so dermatologists must recognize cutaneous cryptococcal infection both clinically and under histopathology. Meningoencephalitis drives mortality in disseminated cryptococcal infection, so the CNS symptoms seen in this patient case must raise suspicion for disseminated Cryptococcus.7 The HIV pandemic led to a spike in incidence in many opportunistic infections, including cryptococcosis.8 Now with an estimated global incidence of 1 million cases per year,4 cryptococcosis must be on the differential for umbilicated papules and nodules, particularly in patients with immunocompromise. Additional settings of immunocompromise include patients with chronic corticosteroid use, solid organ transplants, and chronic tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use.5 Skin-limited disease from traumatic inoculation has been described but is rare.7 If Cryptococcus is identified in the skin, investigation for systemic involvement, especially in the CNS and lungs, is crucial.7

Incorrect stains in answer choices:3

Verhoeff-Van Gieson (choice A) – elastic fibers stain black. Example conditions: pseudoxanthoma elasticum, anetoderma, cutis laxa.

Thioflavin T (choice B) – amyloid stains yellow-green under fluorescence.

Von Kossa (choice D) – calcium salts stain black. Example conditions: calciphylaxis, calcinosis cutis, pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Masson trichrome (choice F) – Mature collagen stains blue-green whereas smooth muscle stains red. Example conditions: scar vs. leiomyoma.

Toluidine blue (choice G) – mast cell granules and mucin stain purple. Example conditions: urticaria pigmentosa, connective tissue disease.

Fite (choice I) – partially acid-fast organisms such as Nocardia and atypical mycobacteria stain pink.

HHV-8 (choice J) – Kaposi sarcoma stains brown.

References:

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, Kay RJ. Chapter 77 – Fungal Diseases. In: Dermatology. 5th Edition. Elsevier; 1343-1375.

- Elston DM. Chapter 18 – Fungal infections. In: Dermatopathology. 3rd Elsevier; 306-320.

- Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Chapter 1 – The basics. In: Dermatopathology. 3rd Elsevier; 1-35.

- Meya DB, Williamson PR. Cryptococcal disease in diverse hosts. N Engl J Med. 2024 May 2;390(17):1597-1610. PMID: 38692293.

- Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):179-206. PMID: 26897067.

- Moe K, Lotsikas-Baggili AJ, Kupiec-Banasikowska A, Kauffman CL. The cutaneous predilection of disseminated cryptococcal infection in organ transplant recipients. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Jul;141(7):913-4. PMID: 16027320.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Feb 1;50(3):291-322. PMID: 20047480.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994 May;30(5 Pt 2):844-8. PMID: 8169258

May 2024 Case Study

Authors: Sara Abdel Azim, MS1,2, Kamaria Nelson, MD1, Karl Saardi, MD1

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

- Georgetown University School of Medicine

A 63-year-old female with a past medical history of substance use disorder and breast cancer status post bilateral mastectomy presented with large, violaceous, hemorrhagic purpuric plaques on the chest and bilateral axilla (Fig 1). She had a fever of 104 F and heart rate of 140 bpm. She was admitted to the hospital for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and was found to be thrombocytopenic with a positive blood culture for streptococcus pyogenes. Coagulation studies revealed a prolonged PTT, an elevated INR level and a low fibrinogen level.

Which of the following is the diagnosis?

A.) Anti-phospholipid syndrome

B.) Calciphylaxis

C.) ANCA associated vasculitis

D.) Purpura fulminans

E.) Warfarin-induced skin necrosis

Correct Answer: D – Purpura fulminans

Explanation/Literature review:

Based on the patient’s manifestation of large, hemorrhagic purpuric plaques, acute systemic infection, and concurrent findings of disseminated intravascular coagulation on laboratory tests, she was diagnosed with purpura fulminans (choice D).

Purpura fulminans is a dermatologic emergency involving dysfunction of hemostasis, leading to a hypercoagulable state and ultimately disseminated intravascular coagulation and dermal vascular thrombosis.1 Patients present with ecchymotic skin lesions that may progress to gangrene and result in amputation. Acute infectious purpura fulminans is the most common subtype and occurs in the setting of sepsis, with endotoxin producing gram-negative bacteria triggering an acquired consumption of protein C and S and antithrombin III. 2,3 The most common pathogens are meningococcus and streptococcus pneumoniae, though streptococcus pyogenes has also been implicated.4

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) (choice A) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, including lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-B2-glycoprotein antibody, that damage endothelial cells and disrupt procoagulation defenses, promoting thrombosis.5 Livedo reticularis the most frequently observed lesion, though APS can also cause ulcerations, digital gangrene, subungual splinter hemorrhages, superficial venous thrombosis, and thrombocytopenic purpura. APS occurs secondary to autoimmune disease, most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus (40% of secondary cases)6 or can be primary. Though infections such as borrelia burgdorferi, treponema, HIV, and leptospira have been implicated in the induction of antiphospholipid antibody formation, septicemia is not a common cause of APS and associated disseminated intravascular coagulation is a less common outcome(choice A).7

Calciphylaxis (choice B) is caused by cutaneous arteriolar calcification that leads to subsequent tissue ischemia.8 It presents as violaceous or erythematous, painful cutaneous lesions or subcutaneous nodules and nonhealing wounds, commonly involving adipose-dense regions such as the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks. Calciphylaxis most commonly presents in patients with end stage renal disease but can also occur in patients with acute renal failure, normal renal function, or early stages of chronic kidney disease.

Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) (choice C) associated vasculitis are a heterogenous group of autoimmune conditions that cause inflammation of blood vessels.9 The most common cutaneous manifestation is palpable purpura, though presentation may consist of polymorphic lesions on a background of livedo reticularis.10 This group of conditions has multisystemic effects, often involving the kidneys, sinopulmonary tract, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs, depending on subtype. Infection should be excluded before making the diagnosis.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis (choice E) occurs in individuals under warfarin treatment with a thrombophilic history or after initiating warfarin therapy with a large loading dose or without concomitant heparin

References

- Bektas F, Soyuncu S. Idiopathic purpura fulminans. Am J Emerg Med. May 2011;29(4):475.e5-6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.04.022

- Perera T, Murphy-Lavoie H. Purpura Fulminans. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Kim MC, Patel J. Recognition and Management of Acute Purpura Fulminans: A Case Report of a Complication of Neisseria meningitidis Bacteremia. Cureus. Mar 04 2021;13(3):e13704. doi:10.7759/cureus.13704

- Okuzono S, Ishimura M, Kanno S, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-purpura fulminans as an invasive form of group A streptococcal infection. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. Jul 09 2018;17(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12941-018-0282-9

- Magdaleno-Tapial J, Valenzuela-Oñate C, Pitarch-Fabregat J, et al. Purpura fulminans-like lesions in antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial C3 deposition. JAAD Case Rep. Oct 2018;4(9):956-958. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.09.006

- Bustamant J, Goyal A, Singhal M. Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430980/

- Asherson RA, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and haematological characteristics of 23 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2005;64(6):943-6. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.026377

- Westphal S, Plumb T. Calciphylaxis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519020/

- Qasim A, Patel J. ANCA Positive Vasculitis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554372/