September 2021 Case Study

by Kamaria Nelson, MD

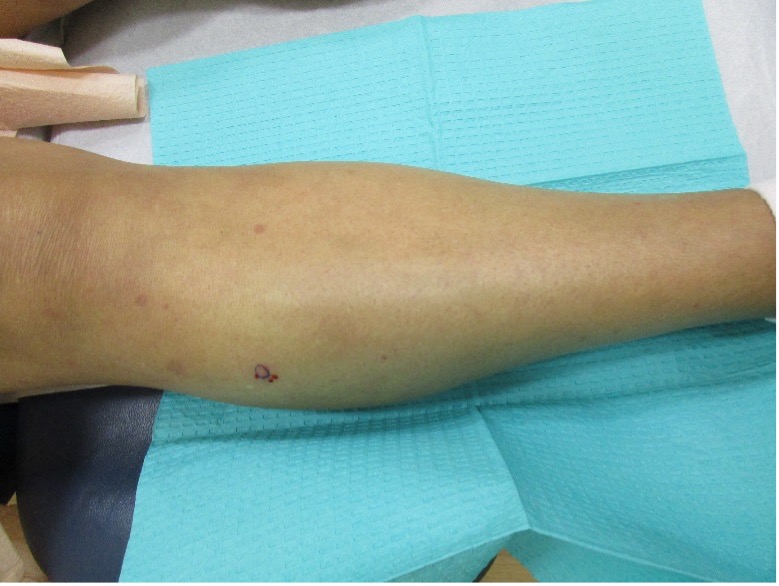

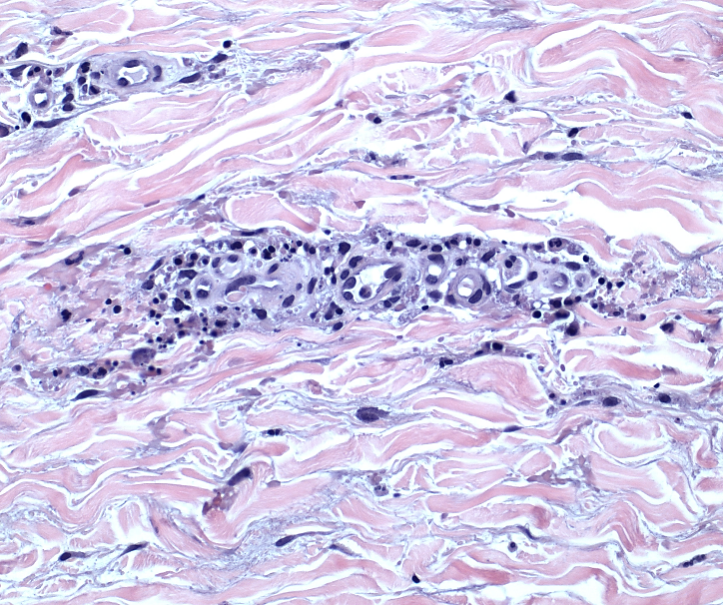

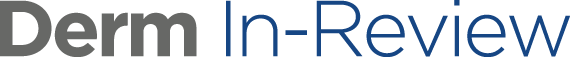

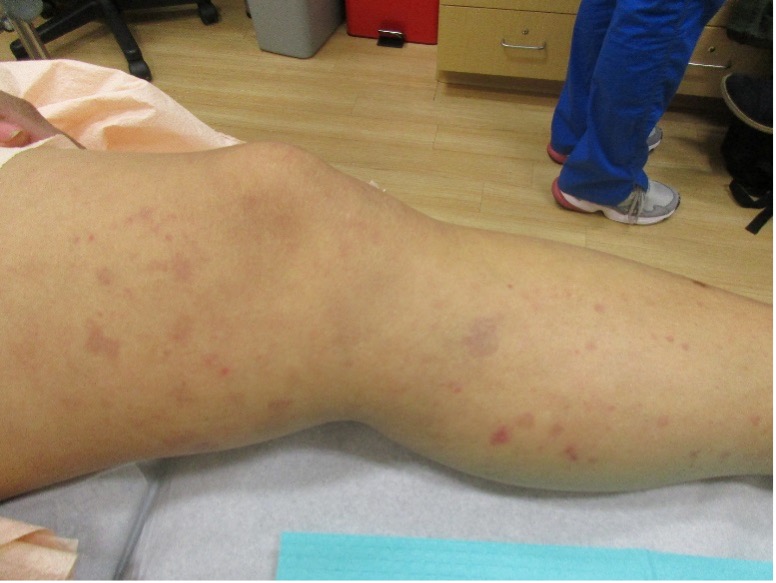

A 51-year-old female with a past medical history of autoimmune hepatitis and mixed connective tissue disease, presents with a recurrent rash on the legs and buttocks for the past 3 months. Patient describes the rash as red and pruritic. The rash occurs every 8 days, lasts for roughly 2-3 days, and resolves leaving “dark spots.” She is currently not using any medication for the rash. Physical exam revealed purple to brown macules and red, thin small plaques on the bilateral thighs and legs (Images 1-2). No lesions noted on the buttocks. A punch biopsy was performed (Images 3-4).

Based upon the patient history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, which laboratory finding is the most important prognostic feature in this skin condition?

A.) Positive ANA

B.) Elevated ESR

C.) Anti-C1q precipitin

D.) Low serum C3/4 levels

E.) Low C1q levels

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is characterized by persistent urticarial lesions lasting for longer than 24 hours with histopathologic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV). Urticarial lesions are present at onset and often resolve with dusky/hyperpigmented patches and plaques after resolution. UV has an incidence of 5 cases/million/year and prevalence of about 5%. It has a slight female predominance and peaks in the 4th and 6th decades of life. Approximately 80% of cases have a benign course and resolve within 3 years. UV has a similar pathogenesis of typical cutaneous small vessel vasculitis except it is thought to be a type III hypersensitivity reaction with antibody complexes that activate complement which triggers mast cell release of inflammatory mediators like TNF-α. This leads to increase of ICAM on mast cells and E-selectin on endothelial cells. There are several precipitating factors of UV including autoimmune connective tissue diseases, infections (i.e. hepatitis B and C), medications (i.e. methotrexate, NSAIDs), hematologic malignancies and rarely solid organ malignancies. Recently, studies have shown UV to be associated with COVID-19 infection.

Work-up for UV includes skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence (DIF) which will reveal leukocytoclasis, fibrinoid deposits around blood vessels, neutrophilic perivascular infiltrate, extravasation of RBCs, and injury and swelling of endothelial cells. DIF will show immunoglobulin and complement deposition around blood vessels. Age-appropriate screening for malignancies is also warranted. Laboratory studies include CBC, CMP, ESR, hepatitis studies, urinalysis, complement studies, C1q levels, and anti-C1q antibody assays. Autoimmune work-up may include ANA, anti-RNP, anti-Smith, Anti-SS-A/B, Anti-Scl-70, Anti-Jo-1, and Anti-Centromere antibodies. The most important prognostic feature is the presence of hypocomplementemia (answer D). Other laboratory findings include elevated ESR (answer B), positive ANA (answer A), presence of anti-C1q precipitin (answer C), and depressed C1q levels (answer E).

Patients with normocomplementemia usually have skin-limited disease and patients with hypocomplementemia have an increased risk of systemic manifestations. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS) is a more severe form of UV and is associated with systemic symptoms. Major criteria include urticaria for 6 months and hypocomplementemia. Minor criteria include vasculitis on biopsy, arthralgia, uveitis, glomerulonephritis, recurrent abdominal pain, and positive C1q precipitin test. In order to diagnose HUVS, patients must meet both major criteria and 2 or more minor criteria.

Treatments for UV is the same for normo and hypocomplementemia. 1st line therapies include antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, indomethacin and dapsone. Other therapies include colchicine, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, dapsone, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil. Rituximab, IVIG, omalizumab, and interleukin-1 inhibitors may be used for recalcitrant hypocomplementemic UV. Treatment is often difficult because of the lack of large randomized controlled trials and there are currently no drugs FDA-approved for use in UV. Symptoms may improve after treatment of underlying conditions in affected patients.

References

- Davis M, van der Hilst J. Mimickers of urticaria: Urticarial vasculitis and autoinflammatory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018. 6(4):1162-1170.

- Bolognia, Jean L., MD; Schaffer, Julie V., MD; Cerroni, Lorenzo, MD. Dermatology, Fourth Edition. 2018.

- Gu SL, Jorizzo JL. Urticarial vasculitis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021 Jan 29;7(3):290-297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.021. PMID: 34222586; PMCID: PMC8243153.

- Magro C, Nuovo G, Mulvey J, Laurence J, Harp J, Crowson AN. The skin as a critical window in unveiling the pathophysiologic principles of COVID-19. Clin Dermatol. 2021 Jul 22. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.07.001. Epub ahead of print. PMCID: PMC8298003.

- Jara LJ, Navarro C, Medina G, Vera-Lastra O, Saavedra MA. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009 Dec;11(6):410-5. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0060-y. PMID: 19922730.