December 2025 Case Study

Savanna Vidal, BS1, Nagasai Adusumilli, MD, MBA1

Reviewed by: Adam Friedman, MD, FAAD1

1Department of Dermatology, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Patient History

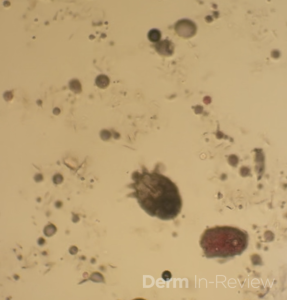

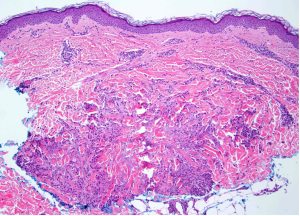

A 30-year-old female with a past medical history of major depressive disorder presented with a severe flare of a lifelong, intermittent dermatitis that had been ongoing for 3 weeks. The flare started after completing a twelve-day prednisone taper and was unresponsive to daily application of fluocinonide 0.05% cream. Throughout the lifelong management of her condition, she had previously failed management with other high-potency topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and intramuscular corticosteroids. Family history was pertinent for similar symptoms in her identical twin sister. On examination, the patient was uncomfortable appearing and was diffusely erythrodermic with pink plaques with thick, desquamative scale distributed on the trunk and extremities (Figures 1 and 2).

Which of the following best explains the mechanism of disease in this patient?

A. Deficient keratinocyte terminal differentiation due to filaggrin gene loss-of-function, leading to Th2-driven inflammation

B. Excessive keratinocyte-derived TSLP production, leading to eosinophil recruitment and atopic diathesis

C. Autoantibody formation against desmoglein 1 and 3, causing intraepidermal acantholysis and inflammatory cascades

D. Unregulated epidermal protease activity due to loss of LEKTI inhibition, resulting in barrier dysfunction and upregulation of Th2 and Th17 pathways

E . Gain-of-function mutation in STAT3 leading to enhanced Th17 differentiation and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis

Correct Answer: D

Explanation/Literature Review

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal recessive genodermatosis caused by loss-of-function mutations in the SPINK5 gene that encodes the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor). As LEKTI normally functions to suppress epidermal kallikrein (KLK), particularly KLK5 and KLK7, skin barrier integrity is disrupted and a complex immunological cascade follows, characterized by heightened Th2 and Th17 inflammatory pathways.1,2

Clinically, NS is defined by the classic triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, trichorrhexis invaginata, and atopic diatheses.1-3 While the overlap of NS with an atopic dermatitis-like presentation may lend itself to a Th2-predominant phenotype, recent molecular profiling has identified significant upregulation of Th17-related cytokines in the erythrodermic variant of NS.2 Pathologic evaluation is nonspecific, exhibiting hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, focal hypergranulosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Immunohistochemical staining for LEKTI may further help with diagnosis, though genetic testing is required for confirmation.1, 4

Topical anti-inflammatory agents, notably corticosteroids, are mainstays in the management of NS, though the increased absorption secondary to the skin barrier defect present in these patients must be considered.1,5 Biologic agents have emerged as promising treatments at the case report level, targeting specific inflammatory axes in NS. Dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antagonist that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, has demonstrated variable clinical efficacy in multiple case series, with an ongoing clinical trial further investigating its efficacy.6 In the erythrodermic phenotype of NS with IL-17 and IL-36 predominant-pathways, IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekinumab have shown remarkable improvement in multiple patients.7-8 The role of other biologics such as TNF-α inhibitors (e.g. infliximab), ustekinumab (IL-12/23 blockade), anakinra (IL-1R antagonist), and omalizumab (anti-IgE) has been explored, but responses remain inconsistent, likely reflecting the heterogeneity of NS immunophenotypes.9 There are no FDA-approved treatments for NS, so all management options mentioned are off-label and may require additional effort from the prescribing clinician to help patients access the medication.

Incorrect Options

A. Filaggrin deficiency is the hallmark of ichthyosis vulgaris and a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis, but not for NS. The pathogenesis in NS is centered on protease dysregulation.10

B. TSLP is a key cytokine in AD and promotes Th2 polarization and eosinophil recruitment, but it is not the primary abnormality in NS.11

C. This describes pemphigus vulgaris, an autoimmune blistering disorder unrelated to NS.12

E. STAT3 gain-of-function mutations are associated with Job syndrome (hyper-IgE syndrome) and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. While both Job syndrome and NS involve elevated IgE, the molecular pathogenesis and cytokine profile differ significantly.13

References

- Herz-Ruelas ME, Chavez-Alvarez S, Garza-Chapa JI, Ocampo-Candiani J, Cab-Morales VA, Kubelis-López DE. Netherton Syndrome: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7(5):346-350. PMID: 34604321.

- Barbieux C, Bonnet des Claustres M, Fahrner M, et al. Netherton syndrome subtypes share IL-17/IL-36 signature with distinct IFN-α and allergic responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(4):1358-1372. PMID: 34543653.

- Drivenes JL, Bygum A. Netherton Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(11):1315. PMID: 36169939.

- Luchsinger I, Knöpfel N, Theiler M, Bonnet des Claustres M, Barbieux C, Schwieger-Briel A, Brunner C, Donghi D, Buettcher M, Meier-Schiesser B, Hovnanian A, Weibel L. Secukinumab Therapy for Netherton Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Aug 1;156(8):907-911. PMID: 32459284.

- Drivenes JL, Bygum A. Netherton Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(11):1315. PMID: 36169939.

- Martin-García C, Godoy E, Cabrera A, Cañueto J, Muñoz-Bellido FJ, Perez-Pazos J, Dávila I. Report of two sisters with Netherton syndrome successfully treated with dupilumab and review of the literature. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2023 Jan-Dec;37:3946320231172881. doi: 10.1177/03946320231172881. PMID: 37200480.

- Barbieux C, Bonnet des Claustres M, de la Brassinne M, et al. Duality of Netherton syndrome manifestations and response to ixekizumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1476-1480. PMID: 32692997.

- Luchsinger I, Knöpfel N, Theiler M, Bonnet des Claustres M, Barbieux C, Schwieger-Briel A, Brunner C, Donghi D, Buettcher M, Meier-Schiesser B, Hovnanian A, Weibel L. Secukinumab Therapy for Netherton Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Aug 1;156(8):907-911. PMID: 32459284.

- Pontone M, Giovannini M, Filippeschi C, et al. Biological treatments for pediatric Netherton syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:1074243. Published 2022 Dec 23. PMID: 36619513.

- Moosbrugger-Martinz V, Leprince C, Méchin MC, et al. Revisiting the Roles of Filaggrin in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5318. Published 2022 May 10. PMID: 35628125.

- Luo J, Zhu Z, Zhai Y, et al. The Role of TSLP in Atopic Dermatitis: From Pathogenetic Molecule to Therapeutical Target. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:7697699. Published 2023 Apr 15. PMID: 37096155.

- Schmidt E, Kasperkiewicz M, Joly P. Pemphigus. Lancet. 2019;394(10201):882-894. PMID: 31498102.

- Tsilifis C, Freeman AF, Gennery AR. STAT3 Hyper-IgE Syndrome-an Update and Unanswered Questions. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(5):864-880. PMID: 33932191.