May 2023 Case Study

by Emily Murphy, MD1, Karl Saardi, MD1

- Department of Dermatology, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

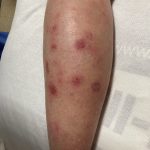

A 65-year-old male with a past medical history of HIV (CD4 count 250, undetectable viral load) and chronic congestion presented with a chief complaint of recurrent cellulitis of the left lower leg. The redness and swelling persisted for 3 months despite antibiotics. On presentation, he had circumferential edema and induration of the left lower leg with erythematous, tender nodules and early bullae (figure 1). A week later, his disease progressed with ulceration and necrosis of these tender nodules (figure 2). A punch biopsy was done, which showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with an angiocentric pattern, composed of large, pleomorphic cells. Extensive necrosis was present with karyorrhetic debris. Immunostains were positive for T cells (CD2), natural killer cells (CD56), and cytotoxicity (granzyme B). A biopsy of the nasal septum showed similar findings. The patient was diagnosed with extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type.

Which virus is part of the diagnostic criteria for this lymphoma?

A.) Human herpesvirus-8

B.) Polyomavirus

C.) Human immunodeficiency virus

D.) Ebstein Bar Virus

E.) Cytomegalovirus

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

Correct Answer: D) Ebstein Bar Virus

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type is an aggressive, non-Hodgkin lymphoma that has four criteria according to the World Health Organization: vascular damage, prominent necrosis, a cytotoxic phenotype, and association with the Ebstein bar virus (EBV, answer D).1,2 EBV positivity is seen in the both the skin and serum. Pathologically, the atypical lymphocytes are positive for cytotoxic markers (granzyme B, peforin), natural killer cell markers (CD2), T cell markers (cytoplasmic CD3), and EBV.1 Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma is rare in the United States, but its incidence is increasing. It is more common in East Asia and Latin America.1

This lymphoma typically affects the upper aerodigestive tract, causing congestion, epistaxis, or necrotizing lesions of the nose or hard palate.1 Other sites can be involved, including the extranasal skin, gastrointestinal tract, testes, or lungs.1,3,4 On the skin, either a generalized morbilliform eruption or purpuric nodules with or without ulceration can be seen.3 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur, but is rare, occurring in only 3% of patients.1

NK/T cell lymphoma has an increased incidence in patients with HIV; a study of 93 patients with this lymphoma found that it occurred at a 15 times higher incidence in patients with HIV compared to the general population.5 However, HIV (choice C) is not part of the diagnostic criteria like EBV. Human herpesvirus-8 (Kaposi sarcoma), Polyomavirus (Merkel Cell Carcinoma), and cytomegalovirus are not associated with Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (choices A, B, E).

Treatment is determined by the Ann Arbor Staging and various prognostic tools, like the PINK-E system (age > 60 years, Stage III/IV, nonnasal primary localization, distant lymph node involvement, and detectable plasma EBV DNA).6 Depending on the stage and prognosis, treatment is typically with an asparaginase-based regimen called SMILE (dexamethasone, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, and etoposide).1,6,7 NK/T cell lymphoma cells are unable to synthesize the amino acid, asparagine, and as this amino acid is depleted with asparaginase, protein synthesis is disrupted and the cells ultimately undergo apoptosis.6 Chemotherapy is typically followed by involved field radiation therapy.1 Various immunotherapies are currently being studied for patients with recalcitrant or relapsed disease as well, including programmed death 1 inhibitors, JAK 3 inhibitors, or anti-CD30 therapies.8 Response to therapy can be monitored with EBV DNA titers, which should decrease with treatment.1

References

- Haverkos BM, Pan Z, Gru AA, et al. Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type (ENKTL-NT): An Update on Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, and Natural History in North American and European Cases. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(6):514-527. doi:10.1007/s11899-016-0355-9

- Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-1714. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268

- Orlowski GM, Tan AJ, Evan-Browning E, Scharf MJ. Primary cutaneous nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma presenting as purpuric nodules on the lower leg. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(10):1075-1078. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.007

- Rahal A, Reddy PS, Alvares C. Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type, Presenting as a Breast Mass. Cureus. 7(12):e408. doi:10.7759/cureus.408

- Castillo J, Pantanowitz L. HIV-Associated NK/T-Cell Lymphomas: A Review of 93 Cases. Blood. 2007;110(11):3457-3457. doi:10.1182/blood.V110.11.3457.3457

- van Doesum JA, Niezink AGH, Huls GA, Beijert M, Diepstra A, van Meerten T. Extranodal Natural Killer/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type: Diagnosis and Treatment. Hemasphere. 2021;5(2):e523. doi:10.1097/HS9.0000000000000523

- Yamaguchi M, Kwong YL, Kim WS, et al. Phase II study of SMILE chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage IV, relapsed, or refractory extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: the NK-Cell Tumor Study Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(33):4410-4416. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6287

- Lv K, Li X, Yu H, Chen X, Zhang M, Wu X. Selection of new immunotherapy targets for NK/T cell lymphoma. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(11):7034-7047.